Once Upon A Time in the Steppes - Part Three

Read Part One // Read Part Two // Read Part Four

Ok, here it is, late as usual; part three of my Mongolian travels.

Sunday morning was gray and cold as we woke up, but sleeping an extra hour helped make up somewhat for the late night of partying it up at "Club Scorpion". Baynaa, Bob the translator from our first tour around Darkhan, and our driver Baatar met us with the van at nine. With Sunday off, we had made a plan to visit Amarbayasgalant Khiid, an old Buddhist monastery and shrine west of Darkhan. After first stopping at the grocery store to pick up bread, sausage, and cheese for a picnic lunch, we drove for about an hour before turning off paved road onto a dirt track. After fording a few small streams — one big lesson learned from our trip in Mongolia was, "cars that you would not necessarily assume to be off-road vehicles, can in fact be used as such" — and driving on for about another hour, we reached the monastery complex at around noon.

Sunday morning was gray and cold as we woke up, but sleeping an extra hour helped make up somewhat for the late night of partying it up at "Club Scorpion". Baynaa, Bob the translator from our first tour around Darkhan, and our driver Baatar met us with the van at nine. With Sunday off, we had made a plan to visit Amarbayasgalant Khiid, an old Buddhist monastery and shrine west of Darkhan. After first stopping at the grocery store to pick up bread, sausage, and cheese for a picnic lunch, we drove for about an hour before turning off paved road onto a dirt track. After fording a few small streams — one big lesson learned from our trip in Mongolia was, "cars that you would not necessarily assume to be off-road vehicles, can in fact be used as such" — and driving on for about another hour, we reached the monastery complex at around noon.  Amarbayasgalant is one of Mongolia's greatest architectural treasures, having survived the advent of the Communists in 1937 with only about a quarter of the complex's temples destroyed. It was built by the Manchu emperor in the 1730s, and as such shares lots of stylistic similarities with other Buddhist temples I've visited in Korea and Japan, though the red ochre walls and wooden roofs gave it a distinctive look of its own. Restoration work supported by UNESCO aid and visitors' fees has been ongoing since 1975 and about 70 monks currently live there, one of whom showed us around the halls.

Amarbayasgalant is one of Mongolia's greatest architectural treasures, having survived the advent of the Communists in 1937 with only about a quarter of the complex's temples destroyed. It was built by the Manchu emperor in the 1730s, and as such shares lots of stylistic similarities with other Buddhist temples I've visited in Korea and Japan, though the red ochre walls and wooden roofs gave it a distinctive look of its own. Restoration work supported by UNESCO aid and visitors' fees has been ongoing since 1975 and about 70 monks currently live there, one of whom showed us around the halls.

After we walked around the main temple complex Baynaa and Bob told us we would be driving further back in the valley to where a collection of stupas was perched on the slope. We left the monastery complex at the valley center, and bounced across the fields in the van. As we approached the stupas we started to pass through stands of birch trees, which stretched out northwards towards the mountains. It was gorgeous countryside for a picnic. We forded a small river running between the birch forest; the stupas were in sight cresting the hilltop ahead of us.

We started to ford another river up ahead... and sunk to a stop.

There are a lot of things to worry about when you're leading a group of eleven people on an international volunteering trip. And I did no shortage of worrying this trip. But there we were, stuck in a river in the middle of nowhere, and I have to say I wasn't worried. Yes, our back wheels were sunk six inches under the riverbed. Yes, after we all carefully tiptoed our way out onto the riverbank on a log (that water was cold) to reduce the weight, and sat back to watch our driver give it a second try, all that produced was a big froth of bubbles and some smoke from our equally submerged tailpipe. Still: not worried. Yes, the monastery was by this point a loooong walk away, and who knows how long it would take us to get back to Darkhan. But you've just got to figure this sort of thing happens a lot in Mongolia, and Baynaa, our driver Bataar, and Bob were clearly doing their best to figure out some sort of solution. So: sit back, relax, enjoy the scenery, and trust the locals to know what they're doing.

Deliverance arrived in the form of four monks (two older, two young boys) in a battered old Russian jeep. We were lucky, since we could've been waiting there for hours; instead it was more like twenty minutes. They happened to be on their way up to the stupas, where there was another small quarters for them, the caretakers. Fishing a rope out of the back of their jeep, we tied it to the front of our van and they lurched forward — only to have the rope fly off with a snap as it broke. Undaunted, Baynaa and Bataar then sprinted up the hill to the monk's house, coming back with a six-foot steel cable that they once again set about securing as we watched and shared some cookies with the two young monks-in-training. With a lurch, a groan of the cable, a splash, and a cheer from us onlookers, the van came free! And so we climbed pack in and carefully made our way up the hill after the monks, coming to a stop next to their house just a few yards away from the stupas and another small shrine.

Deliverance arrived in the form of four monks (two older, two young boys) in a battered old Russian jeep. We were lucky, since we could've been waiting there for hours; instead it was more like twenty minutes. They happened to be on their way up to the stupas, where there was another small quarters for them, the caretakers. Fishing a rope out of the back of their jeep, we tied it to the front of our van and they lurched forward — only to have the rope fly off with a snap as it broke. Undaunted, Baynaa and Bataar then sprinted up the hill to the monk's house, coming back with a six-foot steel cable that they once again set about securing as we watched and shared some cookies with the two young monks-in-training. With a lurch, a groan of the cable, a splash, and a cheer from us onlookers, the van came free! And so we climbed pack in and carefully made our way up the hill after the monks, coming to a stop next to their house just a few yards away from the stupas and another small shrine.We celebrated our escape with a picnic lunch of dried fruit, delicious sausage and cheese, and at this point very crumbly bread. Afterwards one of the monks, a middle-aged fellow who had learned English during a four-year stay in Switzerland, showed us inside the shrine where we admired the paintings and icons. We then hiked up a ways further above the stupas, getting a view of the valley below.

Eventually it was time to head back; the monks accompanied us down, but this time we all got out before the van attempted the river crossing and it went over without a problem. We spent the four hours back playing twenty questions, and had a late dinner at about nine in the evening.

The next day we were back to work, with me on the first house. We started the morning doing some insulation work, filling the cracks between the wall tops and the wooden frames at the roof's base with cut up cement bagging. It was a bit of a slow day, getting back into the work routine, but in the afternoon we began installing "shipu", which is the Mongolian word (actually borrowed from Russian) for the big red fiberglass shingles that formed the house's roof. In the evening we visited a restaurant mentioned in the Lonely Planet, the "Texas Cafe"; I would not necessarily have expected to be eating tex-mex food in Mongolia, but the place itself had all the touches of a US steakhouse chain and the food turned out to be pretty good. In the evening we came back to the hotel and I watched some Mark Wahlberg-is-a-crazy-stalker movie with the others. Bad, extremely bad.

The next day we were back to work, with me on the first house. We started the morning doing some insulation work, filling the cracks between the wall tops and the wooden frames at the roof's base with cut up cement bagging. It was a bit of a slow day, getting back into the work routine, but in the afternoon we began installing "shipu", which is the Mongolian word (actually borrowed from Russian) for the big red fiberglass shingles that formed the house's roof. In the evening we visited a restaurant mentioned in the Lonely Planet, the "Texas Cafe"; I would not necessarily have expected to be eating tex-mex food in Mongolia, but the place itself had all the touches of a US steakhouse chain and the food turned out to be pretty good. In the evening we came back to the hotel and I watched some Mark Wahlberg-is-a-crazy-stalker movie with the others. Bad, extremely bad. Tuesday was our last full day of work, and I spent it working on the second house. The wind was kicking up dust so we were invited inside the family ger, where we all sat around the stove in a circle watching Celine Dion music videos on the small television and making roofing nails, Mongolian-style — cut out a circle of rubber from some old strips of tire, place a bottle cap on top, and pound a nail through the cap and rubber to complete it. We got a pretty good system going between the five of us, and the morning passed quickly; that afternoon I got back up on the roof and helped install more shingles with the construction supervisor Ghana and Chotto the homeowner. We broke early at around four and took a trip to the local "black market", where the others bought clothes and I watched the locals play billiards outdoors. We had another dinner at the Texas cafe, and I spent a while in the local net cafe attempting to catch up on e-mail before preparing to head back and pack up for our departure the next day. That, at least, was the plan.

Tuesday was our last full day of work, and I spent it working on the second house. The wind was kicking up dust so we were invited inside the family ger, where we all sat around the stove in a circle watching Celine Dion music videos on the small television and making roofing nails, Mongolian-style — cut out a circle of rubber from some old strips of tire, place a bottle cap on top, and pound a nail through the cap and rubber to complete it. We got a pretty good system going between the five of us, and the morning passed quickly; that afternoon I got back up on the roof and helped install more shingles with the construction supervisor Ghana and Chotto the homeowner. We broke early at around four and took a trip to the local "black market", where the others bought clothes and I watched the locals play billiards outdoors. We had another dinner at the Texas cafe, and I spent a while in the local net cafe attempting to catch up on e-mail before preparing to head back and pack up for our departure the next day. That, at least, was the plan.So, remember how I said that going to a club in Mongolia was an interesting experience, but that it wasn't necessarily one that I was keen to repeat ("how-did-I-get-myself-into-this" interesting, not "boy-this-is-fun" interesting)? Well... so much for that. Because one disco outing is just not enough, it somehow happened that we were to go clubbing again on our last night in Darkhan — not my idea, I can assure you, but Baynaa and the other Habitat folks seemed enthusiastic when the suggestion reached them. So enthusiastic, in fact, that it became pretty clear they expected that we would all be going again, despite the fact that many of us (me included) were tired and would prefer spending the night packing and preparing for our last morning in Darkhan. Well, being the responsible leader that I am, I went along anyhow, and so got to hear that stupid "Hot Like Me" song, which the Mongolian nightclubs apparently love, for the hundreth time that trip. The club was in what looked like could've been a big observatory dome, except that the floor was ringed by blacklit booths and instead of a telescope there were poles and more strobe lights. The entertainment, besides the bad dance music, was a guy with a shock of dyed blond hair who, if I understood this right, was the winner of "Mongolian Idol" or whatever the equivalent is — though he most just MC'ed rather than any singing. I passed on the dancing and the drinking and sat and squinted some more. I also talked a bit with our driver Bataar, and Baynaa. Baynaa told me he thought I would be a good manager some day. I'm pretty sure he meant that as a compliment so I'll take it as such. This club, like the other one, finally shut down at midnight, at which point we all staggered back to the hotel, where I finished packing, washed some socks in the sink, and finally got to bed at about one in the morning.

The next morning we woke up early, hauled our bags downstairs, and had our last breakfast at the Urtuuchin Hotel. I initially thought we would have to check out entirely, but it turned out we were going to come back for lunch before leaving for UB again, so we piled all of our bags in one room and settled the minibar bills. As we loaded into the van at around nine another dusty pall was hanging in the air — the wind had picked up, strong, and tan clouds obscured much of Darkhan as we drove out to the homes we had helped build for the last time.

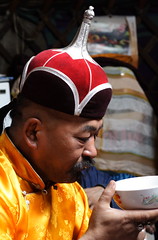

Our first visit was at Chotto's house, where we piled out into the dust storm. We were quickly invited into the family ger, where we saw that we weren't the only visitor — a stocky older man with a big moustache, brilliant orange tunic, and classic Mongolian hat was perched on a stool at the seat of honor opposite the low entryway. He was, it turned out, Chotto's elder brother, visiting from Ulaan Bataar. He was also, incidentally, a bo — a Mongolian shaman. We sat and visited with him for a long time, as he talked with us, asking us about our experiences and thanking us as his brother looked on shyly. Some of our talk was appropriately cryptic as well, such as his personal message to me that "you should ride a camel". At one point he produced a marmot-skin bag, from which he offered us each a handful of blessed rice, which we were told to scatter at a shrine on our travels to bring good fortune, a nice gift to be sure. I have to say having tea with a shaman was a first, and meeting this fellow an experience to remember; definitely not the kind of thing we would've been able to see without the connections we made through our work with the Habitat families. Finally we had to say our thanks and depart for the other home, as it was approaching eleven by that point.

Our first visit was at Chotto's house, where we piled out into the dust storm. We were quickly invited into the family ger, where we saw that we weren't the only visitor — a stocky older man with a big moustache, brilliant orange tunic, and classic Mongolian hat was perched on a stool at the seat of honor opposite the low entryway. He was, it turned out, Chotto's elder brother, visiting from Ulaan Bataar. He was also, incidentally, a bo — a Mongolian shaman. We sat and visited with him for a long time, as he talked with us, asking us about our experiences and thanking us as his brother looked on shyly. Some of our talk was appropriately cryptic as well, such as his personal message to me that "you should ride a camel". At one point he produced a marmot-skin bag, from which he offered us each a handful of blessed rice, which we were told to scatter at a shrine on our travels to bring good fortune, a nice gift to be sure. I have to say having tea with a shaman was a first, and meeting this fellow an experience to remember; definitely not the kind of thing we would've been able to see without the connections we made through our work with the Habitat families. Finally we had to say our thanks and depart for the other home, as it was approaching eleven by that point. Our stop at Ghana's house was somewhat briefer, which was sort of too bad since I had spent most of my time with the crew over there. But the hospitality was equally warm; we took shelter from the dust inside their home, which had just been installed with a door and windows. Inside, Ghana, who is a chef, presented us all a "Thank You" cake, and we celebrated with frosting-covered slices, and a bottle of vodka which we mercifully decided to save until some other time. Far too soon time was up and we had to say our goodbyes; then it was back to the hotel to pay our bills, grab our bags, and have lunch with the Darkhan affiliate staff. With many thanks, we finally said our last goodbyes to our hosts and packed ourselves into the van next to all our bags, heading towards UB and our R&R.

Our stop at Ghana's house was somewhat briefer, which was sort of too bad since I had spent most of my time with the crew over there. But the hospitality was equally warm; we took shelter from the dust inside their home, which had just been installed with a door and windows. Inside, Ghana, who is a chef, presented us all a "Thank You" cake, and we celebrated with frosting-covered slices, and a bottle of vodka which we mercifully decided to save until some other time. Far too soon time was up and we had to say our goodbyes; then it was back to the hotel to pay our bills, grab our bags, and have lunch with the Darkhan affiliate staff. With many thanks, we finally said our last goodbyes to our hosts and packed ourselves into the van next to all our bags, heading towards UB and our R&R.

We arrived there four hours later at the offices of our tour guides, where we met our new driver, an older fellow named Bagi, and translator and guide, a friendly middle-aged woman named Ogi. We passed our bags into the large green Korean tour bus and said our goodbyes to Baynaa and our awesome driver Bataar; they were heading back to Darkhan. We, meanwhile, were heading west to the "Little Gobi" region (not the Gobi desert proper, which is further south and which we would've had to go to by plane), for camping, horseback riding, and other sights.

I notice that I haven't said much about the Mongolian road system yet, which is definitely worth a mention now. In a word, it is bad. It is also, rather frequently, nonexistent. This is not necessarily unexpected in a country with the lowest population density in the world, but still, it made for some rough travel. Infrastructure is something those of us lucky to enjoy it should all seriously appreciate; distances that on paved US highways would've taken perhaps two hours, tops, instead took five or six. The road we travelled on westward from Ulaan Bataar is Mongolian's longest, I believe, and at regular points we swerved off the cracked and potholed surface to follow dirt tracks running parallel — which were there, we soon saw, on account that in several places unfinished drainage ditches split the road surface entirely, forcing you to go off and around. Some day Mongolian road crews may come along and finish those, but I'm pretty sure we spent more time off the road than on; although the tour bus was roomier than the trusty van we came down from Darkhan in, it did not have a lot going for it in the shock absorber department, and our hiking bags would go flying up from the back on regular intervals as we hit a particularly deep bump. Again: it doesn't take an SUV to go offroad. But, there are some times when it might be nice.

As for rest stops, forget it — it was the great outdoors for us when nature called. We made a few brief stops but mostly continued pushing on until late in the night, snacking on bread and dried fruit and watching the steppes roll by. Eventually it got dark, and cold, and we huddled up in the seats in an attempt to catch some sleep; it was after eleven when we finally pulled off onto a long dirt road that finally led us (after a few wheel-spinning stops in the sand) to our ger camp. After unloading we split up into our gers, which were warm and cozy thanks to the fires roaring in the central stoves; we skipped dinner and I fell straight asleep after making the rounds to distribute water bottles to everyone. It was a pretty exhausting day.

As for rest stops, forget it — it was the great outdoors for us when nature called. We made a few brief stops but mostly continued pushing on until late in the night, snacking on bread and dried fruit and watching the steppes roll by. Eventually it got dark, and cold, and we huddled up in the seats in an attempt to catch some sleep; it was after eleven when we finally pulled off onto a long dirt road that finally led us (after a few wheel-spinning stops in the sand) to our ger camp. After unloading we split up into our gers, which were warm and cozy thanks to the fires roaring in the central stoves; we skipped dinner and I fell straight asleep after making the rounds to distribute water bottles to everyone. It was a pretty exhausting day.

The next morning I woke up to the cold — the fire had eventually gone out during the night, and the temperature had plummeted from what we had been experiencing in Darkhan. We were told to expect crazy weather in the Mongolian spring, and we ended up experiencing more or less everything during the two weeks there — dust storms, dry heat, brief rain, shivering cold. It actually stayed cold for the entirety of our R&R period, so it's a good thing I had warned everyone to prepare for it beforehand — up till that point, nobody had thought we were going to actually need our coats and long-sleeve layers, but we had a use for them in the end after all. We had breakfast at the ger camp's "restaurant tent" and met a fellow from Denmark travelling with his father; they had come all this way by rail, amazingly enough, and were continuing on to Lhasa, with the goal of taking the new Himalayan train line recently completed by the Chinese. After chatting with them for a while and warming up on hot tea, we headed out to the windy edge of our camp, where a line of horses were hitched up to two posts. It was horseback riding time!

Ms. Riddarfjarden, with whom I went horseback riding for the very first time ever in New Zealand this past January, was very clear about what I should say when it came time to saddle up, to the point where we practiced several times beforehand: "What are you going to say when they ask you if you've ridden before?" "No, this is my first time." Having gone riding enough times herself to be wary of letting on any experience, for fear of being saddled with an ornery steed, she was adamant that I was not to end up bucking around on any half-tamed beasts. In which I was in full agreement. When it came time to saddle up, however, nobody bothered to ask me anything, and I barely had time to ask "is this a nice horse?" before they had me mount up on a ginger steed with a buzz-cut mane. "Yes", they assured me, he was. Ok, well, we'll see.

Mongolian horses are shorter and stockier than the retired racehorses we rode in New Zealand, which helped mitigate most of the feelings of being perched precariously high above the ground on a semi-intelligent creature that I had felt then (mostly during the times when we went cantering along the rocky riverbeds). They are also, we were warned, shy — don't make loud noises, don't use flash photography, we were warned, unless you want to go flying over the horizon. Duly noted, we assured them. "If your horse takes off, just don't fall off, we'll catch up to you eventually", I half-jokingly told everyone, not wanting to think about what we would do if we had a medical emergency out here in what appeared to be literally the middle of nowhere (the handful of gers where we had spent the night aside), a long and bumpy six hours' drive away from UB. Loaded up with my camera, backpack full of Fearless Leader emergency supplies, and bundled up in jacket, pants, and bandanna, I can't say I quite matched our Mongolian cowboy guides for style, but it was still pretty cool riding out onto the flat open plain around our camp. Four or five of them rode along with the ten of us, teaching us a bit of horsemanship along the way — "giddyup", for the record, is "chu" in Mongolian.

We loped our way across the plain for a while, easing into the saddle. Our horses had just been roped in from a larger herd that was roaming around the plains next to the camp; not wild, I guess, but there were too many of them to have individual names. Mine was handling all right thus far; as one of the last to saddle up, I was towards the rear of the pack. We came to a small stream and began to cross; most of the rest of them were already on the other side when mine stopped for a leisurely drink. I let him go at for a bit, but not wanting to get left behind, I tugged on the reins after a bit and urged him up the bank, muttering "chu!" to him and leaning forward as I tried to catch up. And, well, "chu" he did — off we bolted.

I am told by those who saw the whole thing that it apparently looked like I knew what I was doing. Back straight, head high, reins in hand, whoosh, there I go. Which is good to know. In fact, I was mostly just busy trying not to fall off. My horse sped past the main group, onwards and, it became swiftly apparent, upwards, as he started to head up a hill up ahead. "Pull on the reins!" people shouted after me. "Easier said then done when you're bouncing along at full gallop with a backpack full of first aid kit and a camera bag slung around your side!" I did not respond back, since, as I said, I was too busy following my own advice, keeping both hands gripped firmly on the saddle pommel and working on priority number one, Not Falling Off. "That hill is rocky", I thought to myself. "So what?" my horse thought to itself, and kept going. "There goes another one," our cowboy guides thought to themselves, and one took off to rescue me. Fortunately, however, the hill started to work in my favor as the horse had to slow down enough to the point where I could risk letting going with one hand and hauling back on the reins. He slowed some more, which was good because at about this point one of my feet bounced out of the stirrups. Finally — and when I say finally, I mean, "after possibly a minute or two at most from the start of this all" — he stopped. The young cowboy who had taken off after me pulled up and jumped off, steadying us.

So, uh, yeah, I spent the rest of the morning tied to his horse.

But it was cool. The jarring ride notwithstanding, I think I am starting to develop a taste for horseback riding. My new guide friend even let our horses sprint some towards the end of it — mine appeared to be the most excitable of the bunch, as most of the rest were content with strolling along at a reasonable pace (once actually just up and sat down at one point). I think if we had had more time, we might have gone further into a stretch of desert visible at the edge of the plain, but as it was we were out there for over an hour and I would've been happy to spend an hour more. Except when I got off I found myself bow-legged as hell and intensely sore... but still that was ok. After dismounting, saying our goodbyes to our guides, and wobbling our way back to camp, we had lunch in the ger restaurant and packed up to hit the road, or at least what road we could find.

But it was cool. The jarring ride notwithstanding, I think I am starting to develop a taste for horseback riding. My new guide friend even let our horses sprint some towards the end of it — mine appeared to be the most excitable of the bunch, as most of the rest were content with strolling along at a reasonable pace (once actually just up and sat down at one point). I think if we had had more time, we might have gone further into a stretch of desert visible at the edge of the plain, but as it was we were out there for over an hour and I would've been happy to spend an hour more. Except when I got off I found myself bow-legged as hell and intensely sore... but still that was ok. After dismounting, saying our goodbyes to our guides, and wobbling our way back to camp, we had lunch in the ger restaurant and packed up to hit the road, or at least what road we could find.There's still a good bit left to tell so I'll have to stop here and conclude with part four when I can find the time.